Introduction to web accessibility

What is web accessibility?

Tim Berners Lee (Director of W3C) defines web accessibility as making the web and its services available to all individuals, regardless of their hardware or software, network infrastructure, native language, culture, geographic location, or physical or mental abilities.

Based on this premise, the W3C (the consortium that governs web standards) created the Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) in 1996. Three years later, the first accessibility guidelines (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 1.0, 1999) were published, aimed at encouraging web designers to take accessibility into account. We are currently at WCAG 2.0 (2008), which is being revised due to the advent of mobile interfaces that have changed the way we use the web.

The integration of the standards contained in these reference frameworks aims to provide solutions to overcome users' disabilities when using the web, such as making elements of a web page accessible via keyboard, readable by a screen reader, integrating subtitles into a video, or ensuring sufficient contrast between colors to preserve their visibility and readability in all circumstances. In other words, providing the same level of access to information for everyone, everywhere.

Who is affected?

The user profiles affected by web accessibility are diverse and varied and are not limited to people with disabilities.

Older people are affected, particularly in a context where the population is aging, with all the constraints that this entails, such as declining vision and hearing, motor difficulties, etc.

Foreign nationals, illiterate individuals, and those using obsolete equipment are also affected in the interest of equal access to information.

People with dyslexia or color blindness, who represent 5% and 4% of the French population respectively, have characteristics that must be taken into account.

Of course, web accessibility also aims to make online content accessible to anyone with physical, hearing, cognitive, or visual disabilities.

However, it would be wrong to think that web accessibility only benefits these groups, because in reality it benefits everyone. When taken into account early in the design process, it helps to standardize and clarify the interface. It makes navigation and comprehension easier for users while improving the readability of content. Finally, it provides alternative navigation options in situations where usability is temporarily impaired (noisy environment, poor lighting, broken arm, lost glasses, etc.).

What developments?

When WCAG 1.0 appeared in 1999, WIMP (Windows Icon Menu Pointer) interfaces had already begun the "democratization process" of computers and the web. When thesecond version of WCAG appeared in 2008, the Internet already had 1.6 billion users, there were around 50,000 e-commerce sites in France, and Apple released the second version of its smartphone. Revisions to standards are often the result of developments in technology, usage, and the evolving richness of interfaces and features. It is therefore necessary to reconcile these developments with a detailed analysis of the characteristics and needs of users with disabilities. These factors may explain the significant time lag between the emergence of these new technologies and uses and the revision of accessibility standards, which must take into account the multiple usage situations associated with user profiles. In this article, we will focus on users with visual disabilities and their browsing characteristics.

Illustration of navigation for the blind

Navigation mode

When browsing the web, a sighted person will use visual feedback to point with the mouse at the elements that allow them to access the information they are looking for. A blind user does not have access to this visual feedback from the interface, so they do not know what the interface consists of or how to use a pointing device to operate it. It is therefore necessary to provide them with an intermediary who will "describe" the content of the interface and provide them with an alternative to the mouse for navigation.

A blind user therefore uses assistive tools such as screen readers with speech synthesis or a Braille display to "read" the content of a web page. Keyboard navigation allows them to interact with the interface.

Screen readers

As mentioned above, users need an additional interface to navigate. They will therefore use a technical assistance tool designed primarily for people with visual impairments. The screen reader will read the content of the page through the code, and the speech synthesizer (or Braille display) will transcribe the information displayed on the screen, including both the content and the structure. There are different types of screen readers available on different platforms. Some screen readers are built into the operating system (VoiceOver on Mac or Narrator on Windows), some are browser plug-ins (Chromevox), and others are standalone software programs such as Orca (on Linux), Jaws, or NVDA on Windows, which are currently the most widely used screen readers.

Keyboard navigation

Blind users use keyboard navigation in addition to screen readers. The keyboard allows them to navigate through web pages and interactive and content elements. When used in combination with a screen reader, users can use a series of shortcuts to facilitate navigation. Here is a brief summary of the most commonly used key combinations for navigation:

- TAB: Go to the next interactive element

- Shift + TAB: Return to the previous interactive element

- Insert + Arrow keys: Explore and read the page

- Page Down/Up: Scrolling and managing calendars

- (T) or (F) or (B) or (K): Shortcuts to next (table) or (form field) or (button) or (link)

- Shift + (T) or (F) or (B) or (K): Shortcuts to previous (table) or (form field) or (button) or (link)

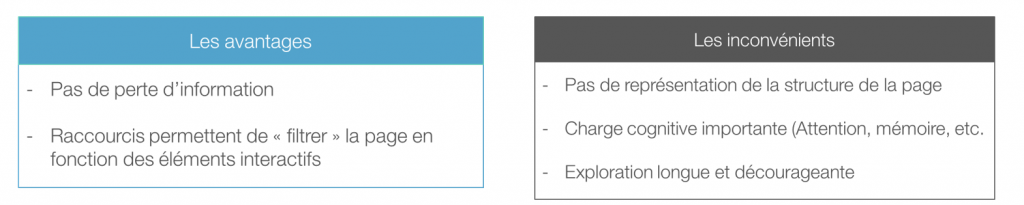

Exploring the pages

Due to keyboard navigation, blind users will discover the page element by element. This is a linear exploration, without being able to visualize the structure and organization of the page as a sighted user could by exploring it spatially.

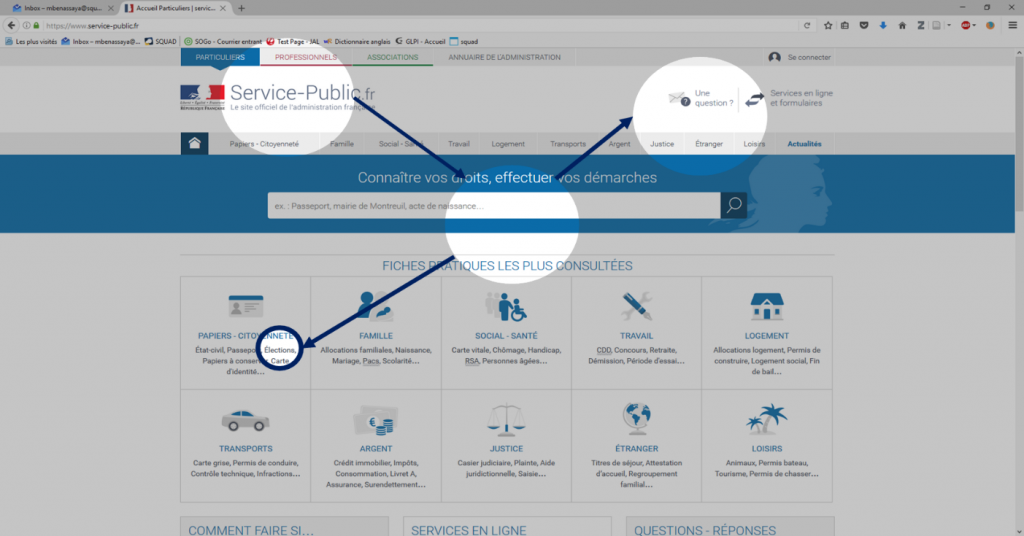

Let's take an example from the service-public.fr website, where information about elections can be found. From the home page, sighted users will explore the page spatially and focus their gaze on different areas (Figure 1). Thus, within a few seconds of visual searching and one click, users can access information about the elections.

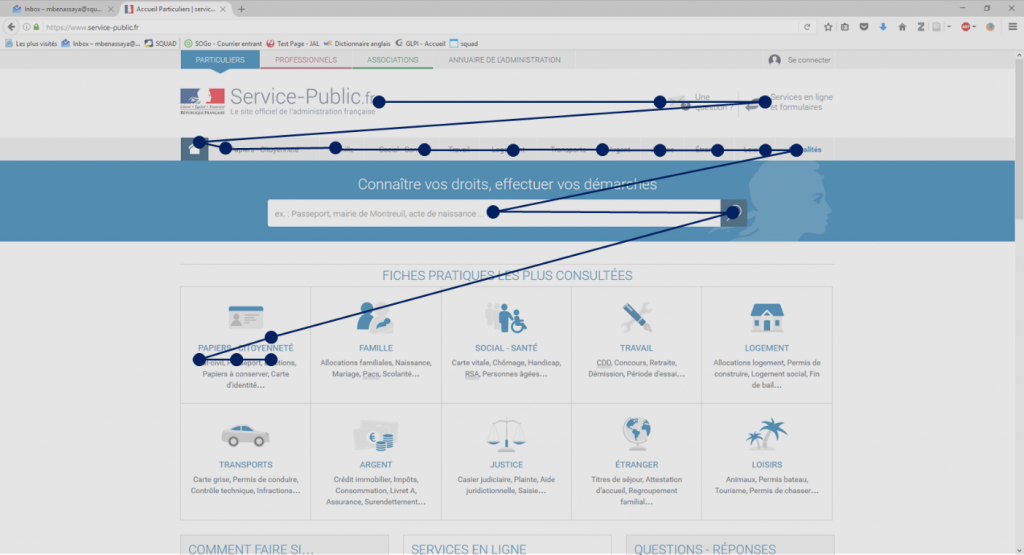

On the other hand, for the same search, a blind user will have to go through each element of the page one by one to find the information. Because of the tools they use to navigate, they have to explore the page in a linear fashion and press the tab key 20 times + press the enter key to access the page on the elections (Figure 2.).

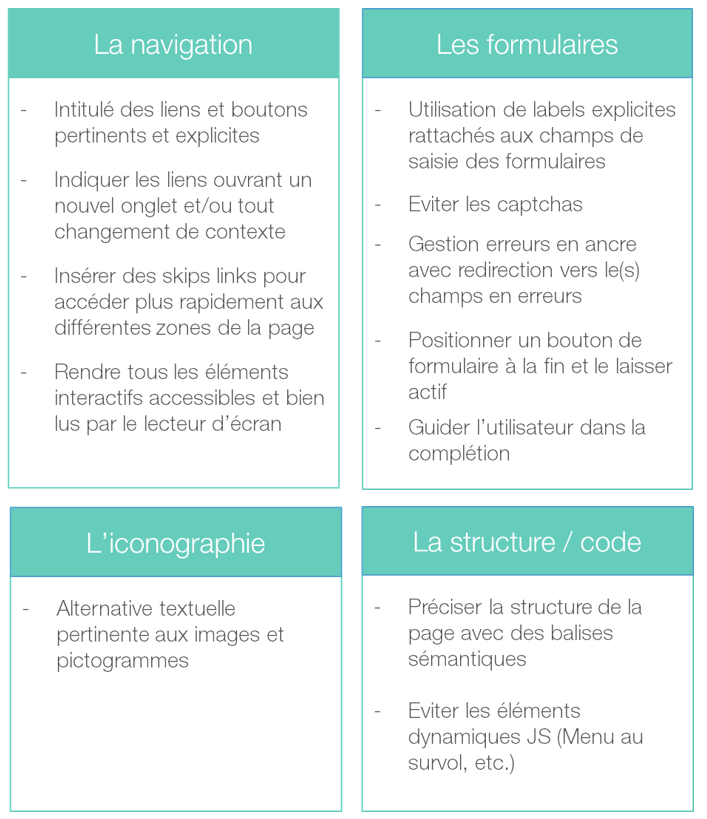

As illustrated above, navigation for blind users is complex and particularly suited to users who are experts in the use of assistive tools and the web in general. However, knowing how to navigate a site does not make it accessible. This is why accessibility standards must be taken into account to ensure access to information at the interface level. To conclude, here is a summary of the main accessibility standards (Figure 4) which, if taken into account early in the design process, can bring a new perspective to the web.